Research#

We study how pathogenic bacteria infect and evolve resistance, using large-scale genetics and chemical biology.

Ultimately, we aim to enable antimicrobial therapies which exploit key weaknesses in the ability of pathogenic bacteria to infect and evolve resistance to antibiotics.

As soon as new antimicrobial drugs are discovered and used in the clinic, pathogenic bacteria inevitably evolve resistance, driving an unsustainable cycle threatening the twentieth century’s improvements to public health.

Grey: Number of antibiotic classes discovered. The curve is modelled as the coupon collector problem, illustrating diminishing returns as we search the same targets and chemical space.

Red: Number of antibiotic classes with clinical resistance. The curve is modelled as exponential decay with a time constant of ~10 years from discovery.

Blue: Number of antibiotic classes without clinical resistance. This curve is the difference between the grey and red curves.

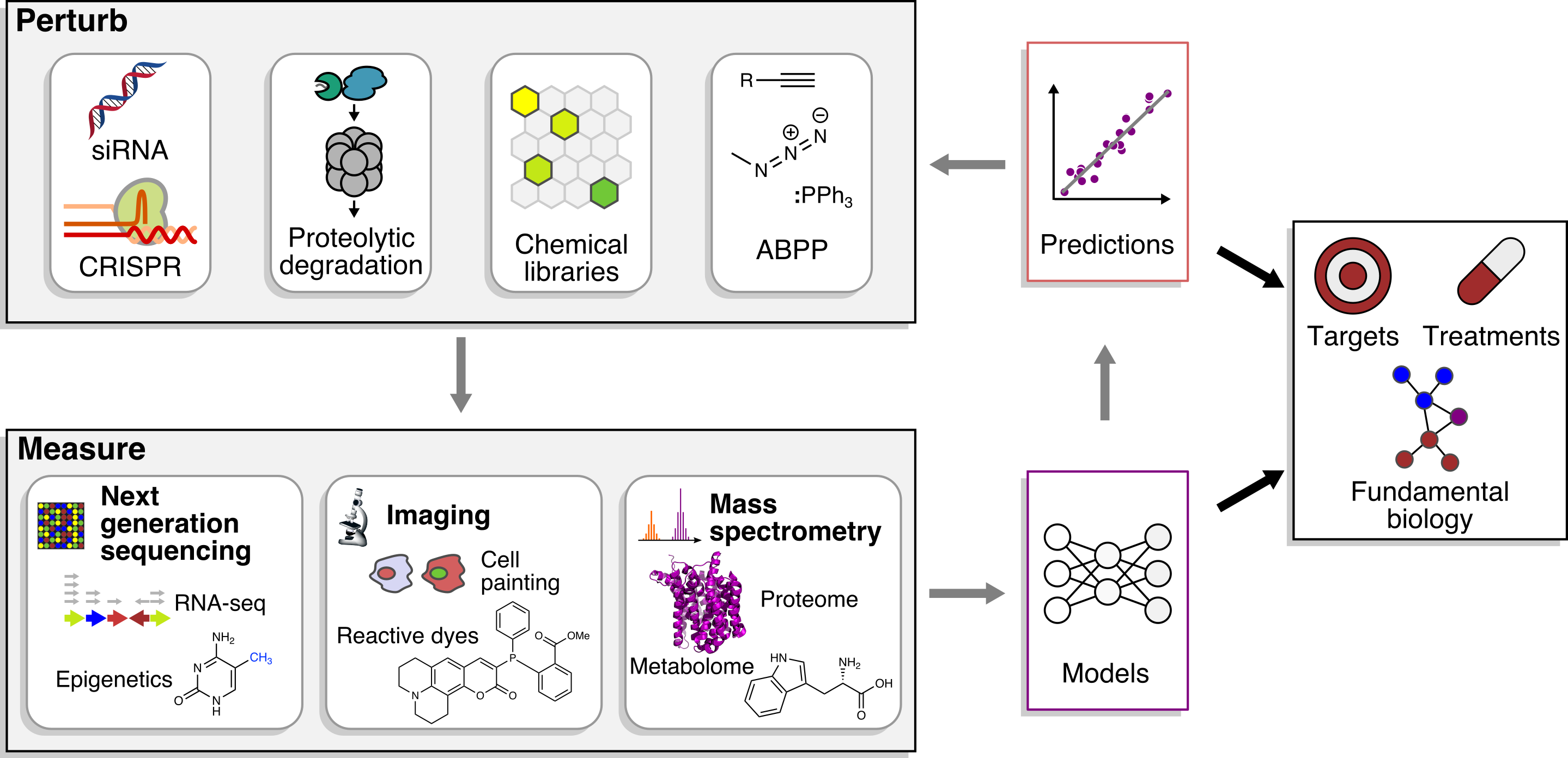

Working at the interface of genetics, chemistry, and machine learning we aim to accelerate the discovery of new chemical probes that precisely disrupt the cellular machinery of pathogenic bacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Klebsiella pneumoniae. With such a toolbox, our goal is to prototype new therapies which interfere with the ability of pathogenic bacteria to survive, infect, and evolve resistance to antibiotics.

With this systems chemical biology approach, we seek to bridge the gap between understanding pathogen biology and designing new therapeutic strategies.

Small molecules complement genetics because they are easily applied to disparate cell types and species, precisely perturb specific functions of multifunctional gene products, and directly bridge the gap between implication of genes in disease and new therapeutics.

Accelerating discovery of new small molecules with new targets#

We aim to develop a toolbox of chemical probes which are active in pathogenic bacteria and which represent diverse, well defined targets.

Rapid target annotation#

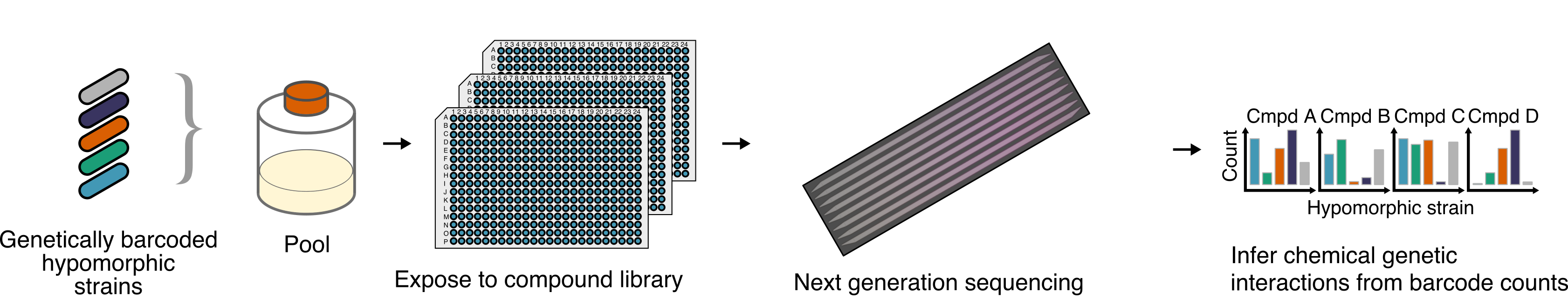

To discover new small molecule perturbagens which act on bacteria against novel targets, we use a chemical-genetic platform called PROSPECT, which uses essential gene mutants’ hypersensitivity to assign targets to new bioactive small molecules. This hypersensitity also allows detection of low potency small molecules which can be later optimised, enabling sparse exploration of chemical space for unexpected new inhibitors of pathogenic bacteria.

Optimising chemical library design#

There are no heuristics analogous to Lipinski’s Rules (forming a cheminformatic definition of “drug-like” molecules) defining the typical chemical space of small molecules which might be active in bacteria. We are using the hypersensitivity of genetic knock-down strains to detect even very low-potency small molecules in order to generate rich, high quality datasets for understanding the chemical features of molecules which inhibit bacterial growth. With this understanding, we aim to design chemical libraries which are optimised for new antibiotic discovery.

Defining targets for bacterial survival and infection#

Alongside developing a chemical probe toolbox, we are usign forward genetics to define targets in pathogenic bacteria which allow them to infect and evolve resistance. With these targets and a toolbox of chemical probes, we will be able to demonstrate new therapeutic modalities, including combination therapies and non-small molecule therapies, which manipulate the ability of pathogenic bacteria to infect and evolve resistance.